I looked her right in the eye and told her she didn’t belong. “This isn’t a knitting circle, Princess,” I spat, towering over her. “The recoil from this rifle will snap your collarbone in two.”

She just stood there, her unnerving calm acting like a mirror to my own ugly pride. She didn’t flinch. She didn’t cry.

I was Gunnery Sergeant Gary Vance. For fifteen years, I decided who became a sniper and who went home crying. And looking at Brenda – 5’2″, maybe 110 pounds soaking wet – I had already decided she was going home.

“I’m just here to observe, Sergeant,” she said softly.

“Observe from the back,” I laughed. The other guys, big corn-fed recruits, snickered. “Don’t get hurt.”

The next morning was the Cold Bore test. 800 yards. High desert wind. It’s the kind of shot that breaks people.

One by one, my best guys stepped up. One by one, they missed. The wind was too unpredictable.

“Impossible conditions,” I muttered, crossing my arms. “Nobody makes this shot today.”

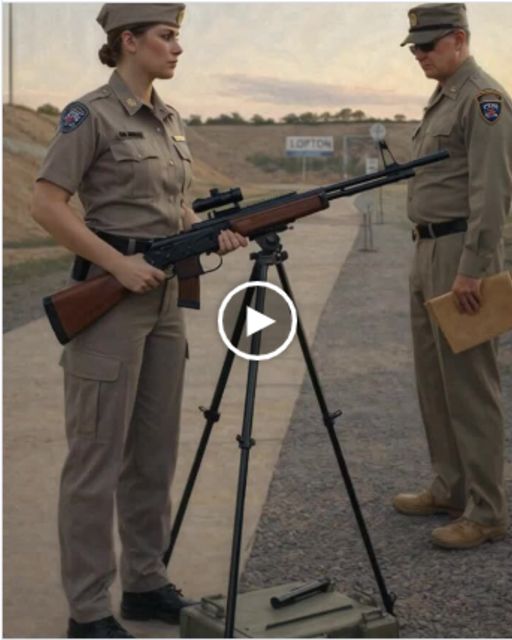

Then I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was Brenda. She was holding an old, weathered rifle that looked like it belonged in a museum.

“May I?” she asked.

I rolled my eyes. “Make it quick, Princess. Then pack your bags.”

She dropped into position. No fancy ballistic computer. No wind meter. She just licked her finger, held it up to the air, and adjusted her scope.

She didn’t hesitate. She exhaled and squeezed the trigger.

CRACK.

The sound echoed across the valley. A second later, the radio crackled from the target pit.

“Center mass. Dead center. Who the hell fired that?”

My jaw hit the dirt. The entire platoon went silent.

Brenda stood up, dusted off her knees, and handed me the rifle. “Windage was three clicks left, Sergeant. Your men were overcompensating.”

I couldn’t speak. I just stared at her. “Who… who taught you that?”

She reached into her pocket and pulled out a folded piece of paper. “I didn’t want to bring this up, Gary. I wanted to see how you treated your recruits first.”

She pressed the paper into my chest.

“But since you asked…”

I unfolded the document. It was a transfer order from the Pentagon. My hands started shaking as I read the clearance level.

She wasn’t a trainee.

I looked up at her, my face draining of color, as she whispered five words that ended my career.

“You are under official review.”

The desert air suddenly felt thin, like I couldn’t get enough of it into my lungs. The smirks on the faces of my recruits had vanished, replaced by wide-eyed confusion.

They were looking at me, then at her, then back at me. They were waiting for me to explode, to assert the authority I had wielded like a club for a decade and a half.

But I had nothing. The club had been snatched from my hands.

She held my gaze, her eyes not filled with triumph, but with a cold, analytical fire. “My name is Major Brenda Evans,” she stated, her voice no longer soft but carrying the unmistakable weight of command.

“The Inspector General’s office has received numerous complaints regarding this training program.”

Major. The word hung in the air, heavy and sharp. I was a Gunnery Sergeant. She outranked me by a country mile.

“Dismiss your men, Gunnery Sergeant,” she ordered. Her tone was flat, leaving no room for argument.

I forced the words out, my own voice a stranger in my ears. “You heard her! Back to the barracks! Now!”

The men scattered, their hushed whispers following them like smoke. In seconds, it was just the two of us, alone under the vast, unforgiving sky.

“In my office, Sergeant,” she said, already walking toward the small, prefabricated building that served as my domain. My kingdom.

I followed her, my boots feeling like lead. The walk that usually filled me with pride felt like a march to the gallows.

Inside, she didn’t sit in the chair reserved for visitors. She walked behind my desk, the one with my nameplate, my photos, my years of service displayed in neat frames, and stood there.

She was claiming my space.

“For the last three years, Gunnery Sergeant Vance, your washout rate has been fifty-two percent,” she began, her voice echoing slightly in the small room. “That’s nearly double the average for a program this advanced.”

I found a sliver of my old self. “I forge the best. The weak don’t make it. That’s the job.”

“Is it?” she countered, her eyes narrowing. “Or do you just break people you decide are weak?”

She leaned forward, her small hands resting on my desk. “I’ve read the exit interviews. The formal complaints. ‘Psychologically abusive.’ ‘Relies on humiliation, not instruction.’ ‘Creates a toxic command climate.’”

She ticked them off like a grocery list. “These are not the words used to describe a man who forges the best, Sergeant. They are the words used to describe a bully.”

The accusation stung more than any physical blow. I had always seen myself as hard, but fair. Necessary.

“I make soldiers who can handle the pressure,” I growled, defending a castle that was already crumbling.

“You make soldiers who are afraid to fail in front of you,” she corrected. “There’s a difference. You weren’t teaching them to manage the wind today. You were waiting for them to fail so you could pounce.”

She was right. I knew she was right. I had relished their misses, each one confirming my belief that the conditions were impossible, that only a legend could make that shot.

A legend like me, I had thought. Not a “princess.”

“Why are you really here, Major?” I asked, my voice barely a whisper. “The IG doesn’t send a Major into the field for a routine review.”

A shadow passed over her features, something deep and personal. “You’re right. This isn’t routine for me.”

She looked at the old rifle she’d set down on my desk. “This was my father’s rifle.”

I stared at the weapon. It was an M40, an older model, but meticulously cared for. The stock was worn smooth in places from years of handling.

“My father was a Marine,” she continued, her voice softening slightly. “He wanted to be a sniper more than anything in the world.”

She paused, letting the silence stretch. “He was here, at this very range, twelve years ago.”

A cold dread, slick and oily, began to seep into my bones. I had trained hundreds, maybe thousands of men. Their faces were a blur.

“He was a smaller man. Not physically imposing,” she said, and her eyes flicked to me, a silent accusation. “He was quiet, but his range scores were flawless. He had a natural talent.”

My mind began to race, flipping through a Rolodex of forgotten faces, of insults I had hurled and forgotten a moment later.

“But his Gunnery Sergeant decided he didn’t have the right ‘look.’ He called him ‘scrawny.’ He told him he lacked the killer instinct.”

I felt the blood drain from my face. I remembered.

Not the name, not at first. But I remembered the man. Quiet. Respectful. A phenomenal shot, but he never boasted. I saw it as weakness. I rode him relentlessly, day after day.

I pushed him, and I pushed him, until one day, he shattered. He just packed his bags and quit. I had chalked it up as a victory, another weak link culled from the herd.

“His name was Michael Evans,” she said, her voice like ice.

Michael Evans. The name clicked into place, and with it came the shame, hot and immediate.

“I remember him,” I admitted, the words tasting like ash. “He was a good shot.”

“He was more than a good shot,” she snapped, the fire returning to her eyes. “He was a good man. And you broke his spirit because he didn’t fit your cartoonish idea of a warrior.”

“You… you’re his daughter?” The question was stupid, obvious, but I had to say it.

“I am,” she confirmed. “He went home, and he never put the uniform back on. But he never stopped shooting.”

She ran a hand along the stock of the old rifle. “He taught me. He taught me everything he knew. How to read the wind, how to control my breathing, how to let the rifle become an extension of my body.”

“He taught me that strength isn’t about how loud you can yell or how big you are. It’s about stillness. It’s about control.”

All my bluster, all my pride, it was gone. I sank into the visitor’s chair, the one she had refused to sit in. I was the visitor here now. An intruder in my own life.

“He died two years ago,” she said, her voice catching for the first time. “A heart attack. The doctors said it was likely exacerbated by stress he’d carried for years.”

She looked directly at me, and for the first time, I saw the pain behind the Major’s insignia. “He spent the rest of his life feeling like a failure because of you.”

I had no defense. No justification. I had built a career on a foundation of casual cruelty, and the bill had finally come due.

The next few days were a special kind of hell. Major Evans didn’t relieve me of duty, which would have been a mercy.

Instead, she made me watch.

She had me run the training exercises as I always had, but she was always there, a silent observer with a notepad.

I’d start to berate a recruit for a bad shot, and I’d feel her eyes on me. The words would die in my throat.

On the third day, a young recruit named Peterson, a lanky kid I’d mentally written off, was struggling with a 1,000-yard shot. He was shaking, his shots going wide every time.

My instinct was to scream, to call him useless, to tell him to go home and cry to his mother.

But before I could speak, Major Evans walked onto the firing line. She didn’t say a word to me.

She knelt beside Peterson. “What are you feeling, Corporal?” she asked, her voice calm and steady.

“My heart’s pounding, Ma’am,” he stammered. “I can’t get it to slow down.”

I would have told him to man up.

“That’s normal,” she said. “It’s just adrenaline. It means you care. Let’s work with it, not against it.”

She didn’t touch his rifle. Instead, she had him un-sight and just breathe. She talked him through a box breathing exercise, in for four, hold for four, out for four, hold for four.

I stood there, watching, feeling useless. I had never taught a recruit how to manage their own biology. I only knew how to punish the symptoms.

“Okay,” she said after a minute. “Your heart rate is still up, but it’s steady now. Don’t fight it. Time your shot between the beats. Find that quiet space. It’s there. You just have to listen for it.”

Peterson nodded, his jaw set. He settled back behind the scope, his movements more deliberate.

He breathed. He waited. And then he fired.

The call came back from the pit a moment later. “Hit. Upper thoracic.”

A wave of relief washed over the kid’s face. It wasn’t a bullseye, but it was a solid, lethal hit. It was a successful shot he’d been incapable of making two minutes earlier.

Major Evans gave his shoulder a light squeeze. “Good work, Corporal. Now do it again.”

She walked back to me, her expression unreadable. “You see, Sergeant? He had the skill. He just needed a tool, not a threat.”

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I sat in my office, staring at the rifle her father had owned.

I had been so proud of my methods. I thought I was creating diamonds under pressure. But maybe I had just been smashing gems into dust.

How many Michael Evanses had I created? How many skilled soldiers had I driven away because they didn’t fit my narrow, brutish mold?

The final day of the review was a complex scenario. A simulated hostage situation where the recruits had to make a single, precise shot through a window on a moving target rig. It was the ultimate test of everything they’d learned.

My top recruit, a big, barrel-chested corporal named Wallace, was up first. He was my guy. Arrogant, aggressive, exactly the kind of man I always championed.

He dropped into position, oozing confidence. But the pressure of the scenario, the ticking clock, the finality of it – it got to him.

His first shot was wide. His second was even worse. He was panicking, his breathing ragged. I could see it from fifty feet away.

“Get it together, Wallace!” I barked, the old instinct flaring up.

Major Evans shot me a look that could have frozen fire.

Wallace was unraveling. He was going to fail. My hand-picked prodigy was choking. In that moment, I didn’t see Wallace. I saw a scared young man.

I saw Michael Evans.

Something inside me broke. The pride. The ego. It all just washed away, leaving behind a raw, aching regret.

I walked onto the line. Wallace looked up at me, expecting a tirade.

“Get up,” I said, my voice quiet.

He scrambled to his feet, looking terrified.

“Breathe with me,” I said. I started the same box breathing exercise she had used with Peterson. I felt foolish, but I did it anyway.

In for four. Hold for four. Out for four. Hold for four.

“Forget the clock,” I told him. “Forget me. Forget the Major. There is only you, the rifle, and the target. Find the quiet space.”

I was using her words.

He looked at me, his eyes filled with a shocked kind of gratitude. He nodded, then got back into position.

He moved slowly, deliberately. He breathed. He waited.

CRACK.

“Target neutralized,” the radio squawked. “Perfect shot.”

Wallace let out a shaky breath and looked back at me, a genuine smile on his face. “Thank you, Gunny.”

I just nodded, my throat too tight to speak. I walked off the line and past Major Evans.

I didn’t look at her, but I felt her watching me.

That evening, I found her packing her gear by her jeep. Her review was over. My career was over. I accepted it.

“Major,” I started, standing a respectful distance away. “I just want to say… I’m sorry.”

She stopped what she was doing and turned to face me.

“I’m sorry for what I did to your father,” I said, the words feeling horribly inadequate. “There’s no excuse. I was arrogant. I was a bully. And I was wrong.”

She studied my face for a long moment. “Yes, you were.”

“Whatever your report says, I deserve it,” I added.

She pulled a folder from her jeep and handed it to me. “Read it.”

I opened it, expecting a recommendation for my immediate discharge. My eyes scanned the final page.

“Recommendation: Gunnery Sergeant Vance to be assigned mandatory leadership and instructional retraining. A probationary period of one year will be instituted, during which he will co-lead the sniper program with a new commanding officer.”

I looked up, confused. “You’re… you’re giving me a second chance?”

“My father wasn’t a vengeful man,” she said softly. “He wouldn’t have wanted your career destroyed. He would have wanted you to learn.”

She paused, her gaze steady. “Today, you showed me that you can learn. Breaking a soldier is easy, Sergeant. Building one is hard. It seems you’re finally ready to do the hard work.”

A weight I hadn’t even realized I was carrying for twelve years finally lifted from my shoulders. It was the weight of unexamined pride.

She offered a crisp salute. “Good luck, Gunnery Sergeant.”

I returned it, my own salute sharper and more heartfelt than any I had given in years. “Thank you, Major.”

Months have passed. I’m not the same man. I co-instruct with a young Lieutenant who has ideas I never would have listened to before.

I teach my recruits how to breathe. I teach them about emotional control. I talk to them, and more importantly, I listen.

Our success rate is the highest it’s ever been. We’re not just creating snipers; we’re building resilient, thoughtful soldiers.

Sometimes, when the wind whips across the high desert range, I think of Major Brenda Evans and her father, Michael. They taught me the most important lesson a marksman can ever learn.

It’s not about having the strongest arms or the sharpest eyes. It’s about having a quiet heart. True strength isn’t in the power you wield over others, but in the humility you find within yourself.