A large plume of crystal meth was expelled by ringleader Damon West as he took another hit, held it for a lengthy count, and then handed the glass pipe to his dealer Tex. The two had turned this shabby Dallas flat into a battleground after robbing so many people and businesses over the course of three years to fund their unquenchable methamphetamine addiction.

BOOM-BOOM. The roar of the bolt-action rifle and lead ripping through the air could be heard by the two. West shouted as a bullet broke the window right next to him. A smoldering canister was tossed into the living area as bright muzzles blazed.

As West sank into the couch, the flash grenade nearly impacted the side of his face. He attempted to glance up, but was only able to feel the assault rifle barrel of the SWAT officer digging into his eye socket. He was blinded by the white lights.

The Dallas Police Department closed in on them on a Wednesday, July 30, 2008, in the late afternoon. Ten days prior, the police had detained Dustin, West’s accomplice in crime, for possession of a stolen vehicle. Twelve members of the Uptown Burglary ring, as they were known, were stoned from narcotics when they broke into hundreds of homes and stole $1 million in goods to buy more drugs. It resembled a scenario from the television series Breaking Bad, but it happened in real life. The circumstances were hopeless.

The SWAT officer yelled to the men, holding a defensive shield along with the rest of the team, “Don’t move.

While pinned to the ground, West was thinking “Don’t worry, Don’t worry,” as the flash finger grenades went off as he lay there confused and high, his hands behind his back.

West, now 47, who had aspirations of playing football, becoming a sports agent, starting a family, and even becoming an elected figure, claims that the Swat team “didn’t just arrest me that day. They rescued me.” “The police busted down the door with guns to pull me outta that world that I was in. They were my angels in life — they just didn’t have wings. They got me out of a situation I could have never gotten myself out of.”

October 1975 to November 2005: From childhood to adulthood

West was raised in a devoted, socially connected family with traditional values. His late father, Bob, worked at Port Arthur News for nearly 40 years as a sportswriter and editor until passing away in July of this year. His mother, Genie, was a nurse. With an elder brother named Brandon and a younger brother named Grayson, West was the middle child. West says that despite having a secure and opulent upbringing, a horrific event altered the path of his life.

When West was nine years old, his 18-year-old female babysitter sexually assaulted him. Being a victim of sexual molestation was embarrassing and terrible on many levels, West said in his 2019 memoir The Change Agent: How a Former College QB Sentenced to Life in Prison Transformed His World. “This babysitter introduced me to a lot of adult behaviors.

Eventually, after six months of abuse, West told his parents about it. “I realized it wasn’t right,” West claims. They felt bad because they hired someone to take care of their children because “my dad was really upset and my mom lost it. I remember her crying—I didn’t see my mom cry a lot. It broke her.”

In the middle of the 1980s, when his parents went to the Port Arthur Police Department to report what had happened, officers allegedly informed them it would be difficult to prove and advised them not to make a report. He started smoking marijuana at age 12 and drinking alcohol at age 10, according to West, who claims that’s when his substance abuse started. As he grew older, further challenges made his drug use worse.

The University of North Texas’ starting quarterback was West. He had an injury in September 1996 during a game against Texas A&M University when three of his shoulder ligaments tore off his distal clavicle bone. West was left as a backup after the procedure and was able to watch his squad from the sidelines. He assisted his fiancée in moving into her new apartment in June of the following year, after playing golf and working out with his teammates. After a long day, I was taking a shower when a towel rack came off the rear wall and broke on the side of the tub. He was rendered unable to walk since it destroyed his left Achilles tendon.

My entire identity was entwined with playing Division I football when that injury occurred, recalls West. When my career came to an end, I was unable to deal with life on its own terms. In order to cope, I began using additional drugs, including cocaine, ecstasy, pills, mushrooms, and pretty much every other substance I could get my hands on.

West partied heavily and rushed the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity in the spring of 1996. When he was no longer able to play sports, he expressed himself through booze, sex, additional drugs, and stealing. He was frequently inebriated and the focal point of trouble on the University of North Texas campus.

West tried to concentrate on his work after earning his degree in 1999. He entered political fundraising after serving as a staff assistant in the US Congress. In 2004, he tried meth for the first time while working as a stockbroker for the United Bank of Switzerland in Dallas, one of the biggest banks in the world.

West, who was known for working into the night, required assistance staying awake, according to him. When one of his coworkers saw him dozing off when the markets were open, they warned him not to do it any longer. In the parking lot of their building, West claims his coworker delivered him crystal methamphetamine and said, “You’re gonna love this stuff.”

Since meth is the most harmful, destructive, and addictive substance that is designed to hook you, West claims that “never have truer words been spoken.” The first time I smoked it, I became immediately addicted.

West was sacked from his position after six weeks. He rapidly realized that his way of life was unsustainable. He had no money left after burning through all of his savings accounts. He was made homeless and in need of additional narcotics after being kicked out of his residence and having his car repossessed. His desire to indulge his addiction developed along with it.

West discovered himself in a world of criminality within the meth houses where he made his camp. He began shoplifting and breaking into automobiles, garages, and storage facilities. He would steal everything, including garage openers, GPS units, and iPods.

West started acting erratically as a result of the meth’s quick-onset urge for more. He frequently committed burglaries in order to satisfy his need to do crimes that paid off right away, despite the significant danger involved. At some point, he started breaking into houses and stole whatever he could.

In the present, West asserts, “I tell people all the time, addicts — for the most part — — they’re not awful people. “They’re sick people who do really bad things, and I was no different from any other addict. When I broke into people’s homes, I didn’t just steal their stuff; I stole something I don’t think my victims will ever get back: their sense of security. And that’s probably gone for good because of my methamphetamine addiction and the decisions I made.”

West’s smile dwindles as he becomes somber. “I could never replace that,” he claims.

Day of Judgment: May 18, 2009

Judge Mike Snipes questioned the jury foreman in a Dallas courtroom in 2009, “I believe that the panel has reached a unanimous verdict. Is that true, sir?

As a federal prosecutor in the Northern District of Texas, Judge Snipes was familiar to West. When they were all hanging out on his yacht in the late 1990s, his friend Rankin Fulbright, a Texas defense lawyer, introduced him to him. When they were in a hip uptown bar in Dallas in the early 2000s, West even bought Judge Snipes a beer. He was currently giving him a prison sentence.

All six days of the trial, West’s parents sat in the first row, behind their son. West remembers thinking at the time, “How much time could a first-time felon, whacked out of his mind on meth while burglarizing dozens of homes but never hurt anyone, expect to receive?”

Jurors were debating whether the judge should sentence him to life without the possibility of parole, his attorney Karen Lambert informed him. The sentence for West may be anything from five to 99 years to life in jail.

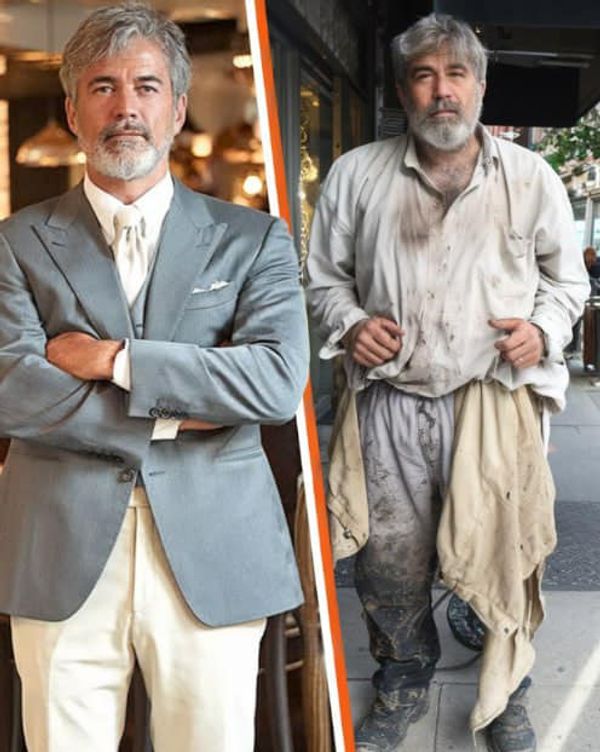

“I was the most privileged guy you could imagine to sit in a courtroom,” West says, recalling feeling anxious and uncertain as he awaited the outcome. This is the quarterback in college, this is the guy who worked on Wall Street, and now he’s this broken man that’s the ringleader of a bunch of other meth addicts breaking into people’s houses. “I am a White middle-class guy who had everything going for me in life. All the advantages, all the privileges, all of the opportunities that a human being could ever have was sitting across from this judge.

In the end, a first-degree felony conviction was given to West. He was thinking about the fact that he was a drug addict, a notorious burglar, and that a jury had just spent 10 minutes deliberating and handing him a 65-year sentence. This was virtually a life sentence for a man in his 30s.

West was in awe. He understood he would be confined and would never be able to cast another ballot. He was ordered to post $1.4 million bail and had a $10,000 debt. But as his sentence began to take effect, it became clear that he would be imprisoned forever. He says, “I own my behavior,” despite this. Nobody likes to hear justifications, and I earned it.

May 2009 to November 2015: From Dallas County Jail to Prison

West chatted with his parents for five minutes following his conviction across a plexiglass barrier. He made a commitment to his mother that he would never get a swastika tattoo or join a gang. He vowed that while doing his time, people would recognize him as a familiar face.

The last sobbing words he uttered before being led away to a life behind bars were, “Mom, I’m scared. I’m so sorry, Dad. I love ya’ll—”

West had just finished a difficult meth detox when he was initially arrested in 2008, and he had no idea how he would make it through the ordeal or what he would do while incarcerated. He merely desired another high.

A few weeks before his trial, he did meet James Lynn Baker II, a seasoned crook. He was a devout man who adopted the name Muhammad after converting to Islam. When he was released from prison, West gave him the nick moniker “Mr. Jackson”. He believed it to be more appropriate.

West was informed by Baker that prison was all about race and that if he didn’t want to join a gang, he would have to fight. Baker advised him, “You don’t have to win all of your fights, but you do have to fight all of your fights.”

The Coffee Bean: A Simple Lesson to Create Positive Change, written by West, is a lengthy account of the Coffee Bean’s history, which Baker then discussed. (Through his Be a Coffee Bean organization, West sponsors 30 kids with incarcerated parents from all over the country, giving them each up to $2,500 per year for the extracurricular activity of their choosing until they are 18).

According to the narrative, Baker instructed West to picture jail as a pot of boiling water in which he should lay three objects—a carrot, an egg, and a coffee bean—and observe how they change.

West was advised to avoid going in hard and then softening after being beaten, raped, or killed. “You don’t want to be the carrot,” he recalls. How about the egg? The egg is protected on the outside by its shell, but as the water boils, the egg’s soft liquid center hardens within. According to West, if an inmate hardens, they lose their capacity for love and risk being institutionalized.

The coffee bean, which has the capacity to produce a pot of coffee, was the final choice. The ability to change the pot, or in this case, West’s sentence to prison, was inside the coffee bean, just as it was within West to change the world.

Before I entered prison, Mr. Jackson gave me the advice to “go out there and be a coffee bean,” recalls West. “I didn’t know how I was going to do it, but I knew I had to make a pot of coffee out of that warm water,” she said.

West gained 55 pounds since his time playing football, and by the time he entered the Mark Stiles Unit in Beaumont, Texas, one of the toughest prisons in the country, he weighed 230 pounds. The adjustment was challenging since he was unfit, overweight, and depressed in county jail.

“I thought I was going to die,” West claims. I didn’t think I would make it after fighting the White gangs before the Black gangs.

West recounts that he was ultimately able to gain the respect of his other inmates after two months of violence and thirty fights. I “got my butt kicked all over that prison,” Mr. Jackson told me, “but I won all my fights because I didn’t have to win, I just had to fight, and that’s really true in life.”

Over 150 times, West’s parents visited him, which always made him feel better. He joined AA and went through the 12-step recovery process after two years, finally rising to the position of chapel clerk. Instead of seeing prison as a punishment, he began to view it as a chance to become the coffee bean.

West sought addiction treatment and developed into a role model prisoner. In honor of his mentor Mr. Jackson, who went away in May 2017 from an opioid overdose, West today gives a $10,000 annual educational scholarship to one Dallas-area youngster with the help of the Baker family. Jackson was West’s mentor.

According to West, serving time in prison was the most difficult thing he has ever done. Being a coffee bean transformed my view on life and made me realize that hope is the only thing that I could find in the hopeless environment of maximum security prisons.

March 2015 through May 1, 2015: Parole Hearing to Release

At his 2015 parole hearing, West was questioned, “Do you think you’ve got too much time?” It is exceedingly unlikely that someone serving a life sentence will ever be granted parole. He was aware that the solution wasn’t simple. If he replied in the affirmative, it would appear that he had not accepted responsibility for his conduct. They might have wanted him to spend extra time if he had said “no.” According to West, “I told her that I owned everything I had done and that I had changed inside the prison.”

The parole board representative opened West’s parole packet on the desk and informed him that he had been doing well in prison and that he wanted to encourage others with his tale. She mentioned that West had a letter from the Beaumont police chief in addition.

“Do you know how many hundreds of letters I’ve read from police chiefs asking us to keep people in prison? I’ve never, in all these years working for parole, seen a letter from a chief asking us to let one of y’all go. Never,” she reportedly told West in his book.

He recalls her responding, “I’ll tell you what I think: I think you got too much time.”

West’s mother called the prison six weeks after his parole hearing to let her son know that she had looked at the parole website to see the outcome of his case. “Damon, the nightmare is over. Baby, you’re coming home,” his mother assured him. “You didn’t get denied. They granted your parole.”

“I started crying,” West admits. “My face was dripping with tears.”

A Fresh Start: November 16, 2015

In 2015, West was picked up by his parents to be taken home after serving seven and a half years in prison. He must submit to regular drug tests, pay $18 in perpetuity, and obtain permission to travel. At 97 years old, he won’t be released from prison until 2073.

West returned to college after leaving prison. He earned his criminal justice master’s degree at Lamar University before joining the faculty of the University of Houston’s downtown campus. The U.S. Army has even adopted the #BeACoffeeBean concept into their resiliency training. He is a motivational speaker for sports teams like the Dallas Cowboys. In addition, West routinely travels to his former prison and developed a prison curriculum that is currently used in Texas.

He claims, “I saw a world that I never would have seen before and I have the power to change it. “When you feel like the face of hope, you never forget the face of hope,” the speaker said.

West began dating nurse practitioner Kendell Romero, his first committed partner, three years after being released from prison. The three of them moved in together after she introduced him to her daughter Clara after a period of time.

The pair got married a year later, precisely 10 years to the day after West was given a life sentence. West responds while fighting back tears, “I get emotional talking about this. For a guy like myself who had made the decisions I had, “I didn’t think it was one of those things that was possible.”

West raises his head and exhales deeply. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice and the parole board view me as an ally and a somebody they can come to for assistance within the jails. “I do think people can change. Look at me. I mean, look at my life. I’m proof of it,” he adds. “I’m the one they can point to and say that treatment works,” he said.

But West is of the opinion that it takes a village. He emphasizes the necessity for resources and assistance for those who are released from prison.

They also require pardoning. “I think that’s something that society has to change. We’ve got to be more accepting of the fact that people can’t undo what they did wrong, but people do deserve that second chance,” West adds. Anyone can be a coffee bean if I can.