Shakereh Khaleeli was “rich and beautiful” and descended from one of the most aristocratic families in Karnataka, a southern Indian state. However, the wealthy heiress went missing in 1991, and it appeared that she had vanished into thin air.

Her second spouse, Murali Manohar Mishra, better known as Swami Shraddhananda, cooked up wonderful stories about her whereabouts for three years.

Her remains were discovered in 1994 beneath the courtyard of their opulent home in Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore). Shakereh had been drugged, placed in a wooden casket, and buried alive, it was later revealed.

The trial court convicted Shraddhananda of murder in 2003 and sentenced him to death, which the high court eventually upheld. The courts agreed that he pursued and married Shakereh in order to benefit from her money and properties worth billions of rupees.

During his appeal, the Supreme Court described the case as one of “a man’s vile greed combined with the devil’s cunning,” but commuted his sentence to life in prison “without remission.” Last week, the Supreme Court denied his request for parole.

The horrific crime that shook India 30 years ago is the topic of a new web program called Dancing on the Grave, which is available on Amazon Prime Video and is titled after the dance parties Shraddhananda allegedly held in the courtyard where his wife was buried.

According to Chandni Ahlawat Dabas, producer of India Today Originals Production, there were “whats, whys, and hows” surrounding this tragedy that seemed implausible.

“Despite being 30 years old, we felt that this was a crime that needed to be shared because it’s still such a mystery even today,” she continues.

The series about the murder – and the culprit – does not resolve all of the concerns, but it is an engrossing watch that has gotten a lot of attention in India.

Shakereh’s life is explored in the first two episodes of the four-part series.

She married the dashing diplomat Akbar Khaleeli and had four daughters. She was the granddaughter of Sir Mirza Ismail, who served as the Dewan of the princely states of Mysore, Bangalore, Jaipur, and Hyderabad and is associated with the construction of various major structures and monuments.

Family relatives remember her as “a charming, larger-than-life character” who was “very social, very loving and loveable” and “fond of vintage cars.”

But in the mid-1980s, she met Shraddhananda, and her life changed dramatically.

According to BBC Hindi’s Imran Qureshi, who worked for the Times of India in Bangalore at the time and appears in the docuseries, “the murder shocked people primarily because of the manner in which she was killed – the fact that she was buried alive.”

He says that the crime “became the talk of the town because Shakereh had married a man like Shraddhananda after divorcing her first husband.”

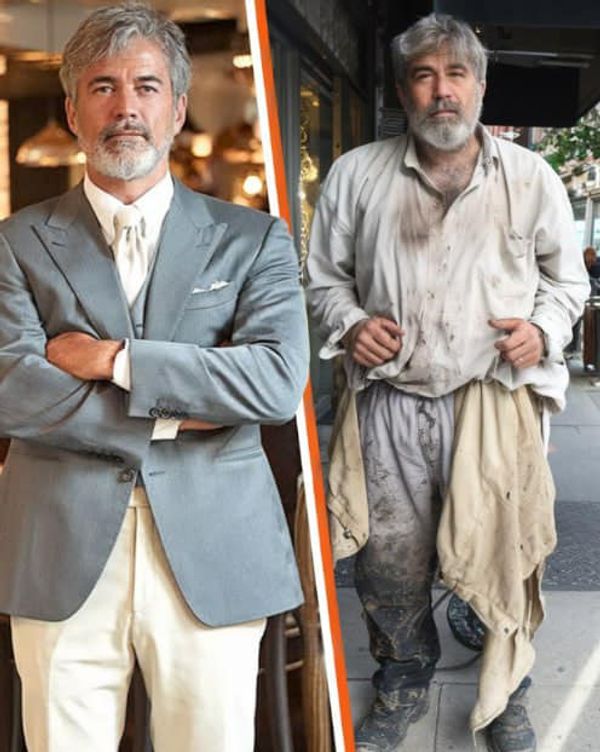

Shraddhananda was described as a “fake holy man” and a “errand boy” who endeared himself to Shakereh by “helping resolve some property matters” for her and “exploiting her desire to have a son by claiming magical powers” in press clippings from the time.

According to reports, their marriage began to fall apart soon after their marriage in 1986, and the two quarrelled frequently, usually over money, leading Shraddhananda to plot to assassinate his wife in such a heinous manner.

Despite the fact that he was found guilty by a total of eight judges from India’s trial court, high court, and Supreme Court, his lawyer claims that the evidence against him is at best circumstantial – and we hear from Shraddhananda himself in the web series, who still denies his crime.

Some have questioned the show’s decision to give a platform to a convicted murderer, but Patrick Graham, the Mumbai-based British filmmaker who co-wrote and directed Dancing on the Grave, defends the decision.

“I believe it is critical that we hear his side of the story, especially since we haven’t heard from him in the last 30 years.” Furthermore, he provided us with invaluable insight into Shakereh’s character,” he told the BBC.

Graham said that the crew went into the jail to find out how someone like Shakereh might be convinced by someone like Shraddhananda.

“But he also swayed us initially into believing that there were layers to the story, even though none of us had any doubts about his crime by the time we finished with him.”

They went in “wary of coming across as bullies to this very small, frail, old man,” he says. But as we learned more about the narrative and talked with him, we began to suspect that he had an agenda, that he was playing us, that he was telling a yarn.”

“The more time we spent with him, the clearer it became to us that his feelings were not genuine, and towards the end, we tried to have a more robust conversation with him,” Graham explains.

And this, he claims, triggered Shraddhananda’s “rant,” with him “insisting that he was innocent, that he was being treated unfairly.”

According to Graham, most true crime shows portray criminals as “genius.”

“But I was emphatic that I did not want to do that.” Of course, Shraddhananda had a few talents, one of which was convincing others to trust him,” he says.

But, in the end, he was unable to persuade the Indian courts of his innocence.