They Knocked Down the Boy With the Metal Leg and Mocked Him—Seconds Later, His Father Walked Onto the Playground in Full Tactical Gear and Said Calmly, “I Just Saw My Disabled Son Get Slammed Into the Dirt. If He’s Getting Suspended, Call Me. If I’m Getting Arrested, Call the Cops. But We’re Leaving.” The Principal’s Grin Vanished Instantly. 😱 😱

The silence that fell over the playground wasn’t the peaceful kind.

It felt like the kind of silence that comes after something explodes—when your hearing rings, your vision narrows, and nothing feels quite right.

Just moments earlier, the playground was its usual mess: shouts, bouncing balls, shoes pounding the blacktop, and a distant whistle from the basketball court. Then it happened. Mason gave me a hard shove.

My prosthetic leg clipped the edge of the curb.

The joint froze. The world flipped.

I hit the ground hard—shoulder first—my carbon fiber leg grinding against the pavement. Someone nearby let out a laugh. Another voice said, “Did you see that?”

At first, I didn’t even understand what they were reacting to. I was just trying to catch my breath, blinking through the sting in my knee and the sharper sting of humiliation. My cheek was pressed to the gritty pavement, the scent of dust and old playground chalk filling my nose.

And then I felt it.

A strong, gloved hand wrapped around mine. Firm, steady. Not rough—reassuring.

“Easy, Leo,” came a voice, low and calm. “I’ve got you.”

I recognized it instantly.

I’d heard that voice in my dreams, in garbled phone calls, in recorded birthday messages sent from halfway across the world.

Dad.

I tilted my head up.

There he stood—gear still on, helmet under his arm, the dust of another continent still clinging to his uniform. His face looked older, the crease lines deeper. A pale scar now cut across his eyebrow—a mark he didn’t have when he left nearly two years ago.

But he was here.

Real. Present. Solid.

And he was staring at my leg like it was the only thing in the world that mattered.

“You okay to walk?” he asked in a voice meant only for me.

“Yeah,” I answered, though it came out unsteady. “The joint locked up when I hit the ground. I just need to fix it.”

He dropped to one knee on the wet pavement without hesitation, not caring about the mess soaking into his uniform. With the precision of someone used to handling delicate gear under pressure, he checked the leg.

“The pin’s jammed,” he muttered. “Hold still.”

A quick adjustment. A soft click.

The joint unlocked.

“Try it now,” he said.

I moved my leg. It swung naturally. The ache eased.

“All set,” he said, standing.

“Thanks, Dad,” I murmured.

“Sir! Sir, I need you to step away!”

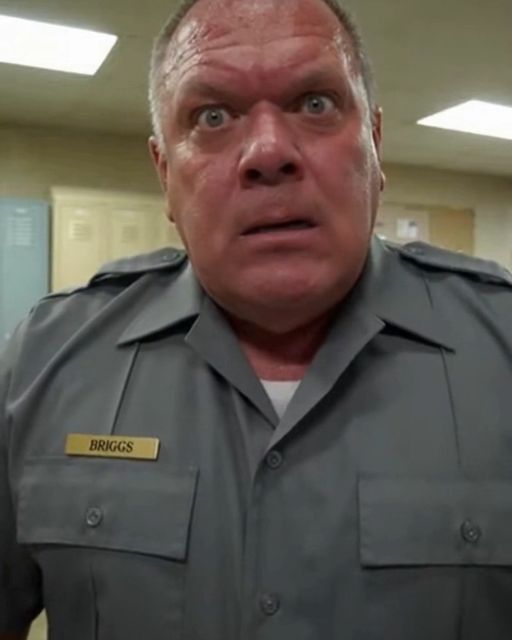

The shout came from Mr. Henderson, the school’s security guard, puffing as he rushed toward us. His reflective vest was crooked, and his hand hovered near his radio like it was a panic button.

“You’re not allowed on campus—this is school property!”

My father doesn’t even blink.

He steps slightly in front of me, placing himself between me and Mr. Henderson like a human shield made of Kevlar and certainty. His voice doesn’t rise; it doesn’t need to. It’s calm, clipped, military-grade authority distilled into a single sentence.

“I just saw my disabled son get slammed into the dirt,” he says. “If he’s getting suspended, call me. If I’m getting arrested, call the cops. But we’re leaving.”

The air tightens around those words. Every kid, every teacher, even the lunch lady frozen mid–tater tot scoop, is watching.

The principal, Mr. Grady, comes jogging up now, his polished shoes clicking too fast against the pavement. He flashes a rehearsed, too-wide smile that doesn’t reach his eyes.

“Mr. Parker,” he says, breathless, “let’s not escalate things.”

Dad doesn’t flinch. “You let them slam him into the ground.”

“That’s not exactly what happened,” Mr. Grady offers quickly, already sweating through his button-down. “I’m sure there’s context—”

“My son was walking. A kid shoved him. He fell. I was watching from the parking lot. I don’t need context. I need accountability.”

Someone behind us gasps.

Mr. Henderson reaches for his radio again. “Sir, if you don’t leave—”

Dad tilts his head, just slightly, and in that quiet moment, the soldier in him surfaces.

“I have been shot at in countries your history class doesn’t cover,” he says evenly, eyes locked on the guard. “I’m not raising my voice. I’m not being violent. But I will not let you act like I’m the problem for picking up my son.”

Henderson’s hand drops away from the radio.

“Leo,” Dad says to me now, turning his body slightly. “Can you walk to the truck?”

“I can,” I say, stronger this time.

Dad nods once. “Then let’s go.”

We start walking. Every step echoes. The whispering around us is low but unmistakable.

“Is that his dad?”

“He just walked in like Iron Man…”

“Mason’s dead.”

I glance toward the group of kids still clustered near the basketball court. Mason is standing a few feet behind them, pale, his jaw clenched tight. One of the teachers finally pulls him aside.

Good.

But it doesn’t fix the knot in my stomach. The ache in my knee has dulled, but the other pain—the kind that comes from being watched, judged, laughed at—still burns under my ribs.

We reach the gate. The moment Dad pushes it open, a voice shouts from behind us.

“Wait!”

We both turn.

A woman is hurrying from the main office building, a clipboard clutched to her chest. Her name tag reads “Mrs. Timmons – Counselor.” She slows as she reaches us, trying to look collected.

“Mr. Parker,” she begins carefully, “please. I think there’s been a misunderstanding. We want to support Leo, truly, but—”

“Support?” Dad cuts in. “Do you know how long it took me to convince him to come back to school after he got this leg? Two years of surgeries, fittings, training, and mental hurdles just to walk again. And now he gets knocked down for fun, and no one does a thing until I show up?”

Mrs. Timmons frowns, clearly unsure how to respond.

“We’ll review the incident,” she says. “We have security footage—”

“Good. Review it. While you’re at it, review your bullying policy,” Dad replies. “And your lack of staff presence during recess. And maybe train your people not to treat parents like criminals when they come to help their injured kids.”

The counselor opens her mouth again, but nothing comes out.

Dad doesn’t wait. He looks at me and says, “Truck. Now.”

We leave.

The truck smells like pine and engine oil. Familiar. Safe. Dad starts it, but doesn’t put it in gear. Instead, he sits back, staring out the windshield with his jaw tight.

I wait.

Then, finally, he speaks. “How often does this happen, Leo?”

My throat tightens.

“It’s not always like that,” I say. “Sometimes it’s just jokes. Or they bump me and say it’s an accident. Or they call me names.”

He nods slowly, absorbing each word like shrapnel.

“Do you tell anyone?”

“Mom knows,” I say. “But I told her I could handle it.”

He turns to me, eyes sharp. “You don’t have to handle that alone. That’s not strength, son. That’s survival. And I didn’t fight through two deployments so you could be bullied in your own country.”

I swallow hard. “I didn’t want to be the kid who tattles.”

“You’re not,” he says. “You’re the kid who deserves to walk across a playground without being shoved to the ground. Prosthetic or not.”

The silence between us now is different—heavy, yes, but also warm. It’s laced with something I haven’t felt in a long time.

Protection.

After a moment, Dad shifts into gear. “Let’s get ice cream.”

I blink. “What?”

“Ice cream,” he says, as if it’s obvious. “You got body-slammed by a future ex-con with anger issues. We’re getting sprinkles.”

I laugh before I can stop it.

The tension breaks. The knot in my stomach loosens just a little.

We pull into a small ice cream shop on the edge of town. Dad insists I take the booth while he orders. When he returns, he sets down two sundaes loaded with enough toppings to feed a family.

He doesn’t press me with questions. Instead, he talks about his deployment—about a stray dog his unit adopted, about a local kid who sold them mangoes every week, about the stars in the desert sky.

I listen. I laugh. I forget, for a moment, about the playground.

But then I see it.

A group of kids from school walks by the window. One of them pauses, spots me, and points. They whisper to each other. Mason is with them.

My spine stiffens. I wait for Dad to notice.

He does.

But instead of reacting with tension, he picks up his spoon and waves it casually at them through the glass. His face is calm, almost amused.

They scatter.

“What just happened?” I ask.

Dad shrugs. “Sometimes the uniform talks louder than words.”

I shake my head. “They’re going to make me miserable on Monday.”

He leans forward, expression serious now. “Not if we don’t let them.”

I frown. “What do you mean?”

“We go back Monday. Together. I walk you in. You hold your head up. You show them that falling doesn’t define you—getting back up does.”

“But what if they laugh again?”

“Then we keep walking,” he says. “Because fear feeds bullies. But confidence? Confidence starves them.”

I look down at my sundae. “I don’t feel confident.”

“You don’t have to feel it to choose it,” he says quietly. “You just have to stand up. That’s all.”

I nod, slowly. Let the words settle into me.

Stand up. That’s all.

When we pull into the driveway later, Mom comes rushing out, her eyes wide.

“You’re supposed to be in uniform debrief right now!” she says to Dad.

“I was,” he replies. “But Leo needed me.”

She turns to me, her eyes immediately scanning for injuries. “What happened?”

Before I can speak, Dad steps back and gestures toward me.

“Let him tell it.”

I do.

For the first time, I say everything. Not just the fall. The comments. The way they look at my leg like it’s a malfunction instead of a miracle. I tell them about the jokes I pretend not to hear and the moments I fake a smile so no one sees the sting.

Mom listens, silent, her hand over her mouth.

Dad listens, too, his arms crossed.

When I finish, they both kneel in front of me. I expect a lecture. Or pity.

But what I get instead is a promise.

“We’ve got your back,” Mom says.

“Always,” Dad adds.

I believe them.

That night, I charge my leg. I pack my bag. I lay out my cleanest clothes.

And in the morning, when I step through the school gate, my dad is beside me—his uniform gone, but his presence just as solid. The kids watch. Some whisper. But none come near.

I take each step like it matters.

Because it does.

I’m not invisible.

I’m not broken.

And I’m not alone.